Did China Choose The Right Time to Open Up?

Many in China are saying "yes"; I disagree. Below, I explain why, and discuss measures that would make it safe to open up.

Introduction

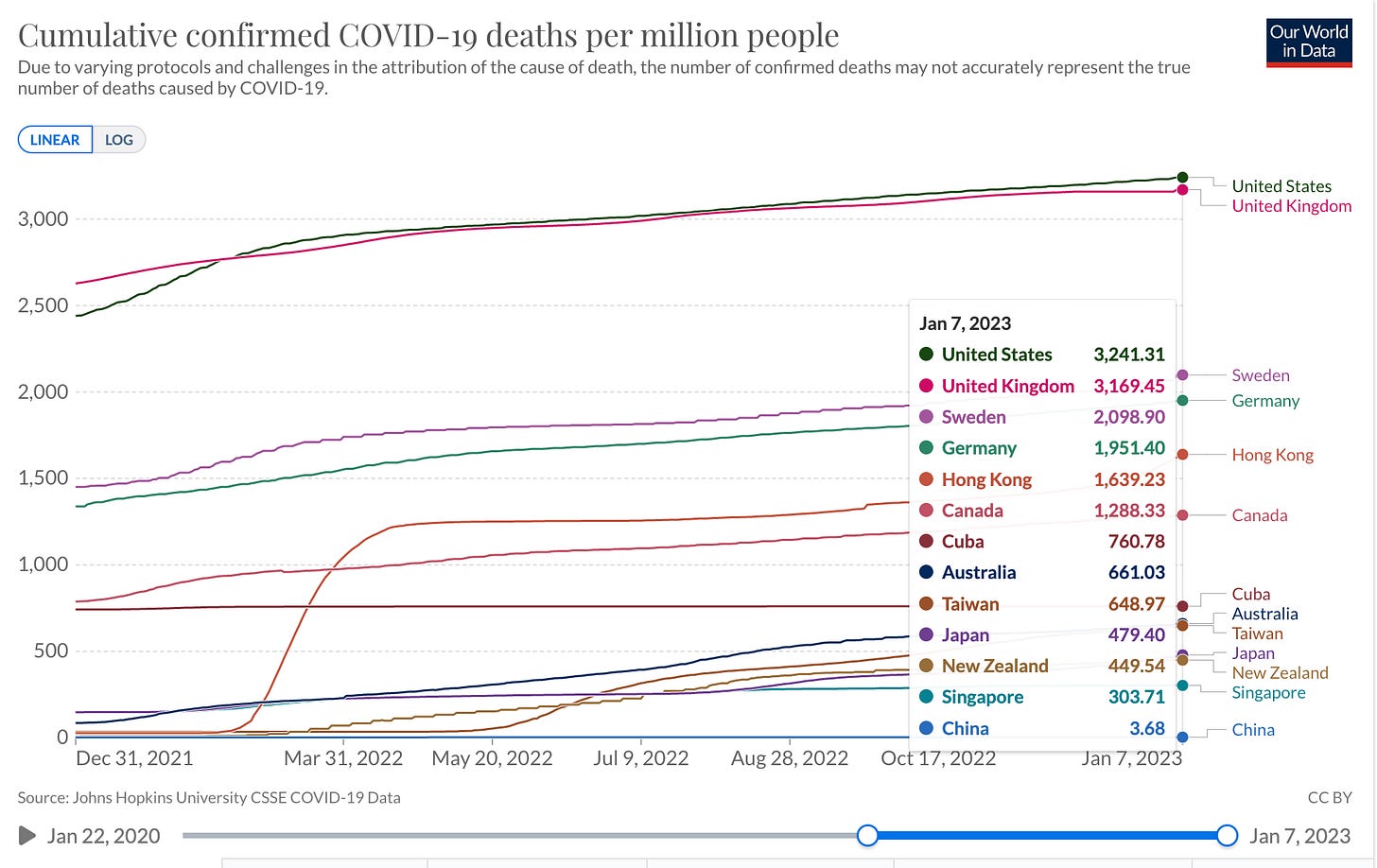

In a recent video, I discussed how massively successful mainland China’s dynamic zero COVID policy that it pursued until recently has been. Its death rate from COVID has been a tiny fraction of what it’s been in Western countries and is even significantly lower than in countries such as Japan and Cuba that have taken COVID very seriously. As the saying goes, a picture is worth a thousand words.

Even the Western media, despite being massively biased against China, were forced to acknowledge that (mainland) China had contained COVID quite well. Instead, the tack taken was “Yeah, China has kept mass death from occurring like it has in the West, but at what cost?” Despite widespread popular support among Chinese people for their government’s COVID containment policies, at least until recently, China’s zero COVID policies have been used as an opportunity to attack the Chinese government as “authoritarian,” or falsely portray it as having caused draconian economic damage despite China having the best economic performance in the world during the recession-plagued COVID era. But it is easily demonstrable that, due to the specific nature of China’s policies, we can be confident that they really have had very low infection and death rates—and the benefits far outweighed the costs.

How Did Zero COVID Work?

From the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 up until late 2022, China pursued what has come to be called its “dynamic zero-COVID” policy. The policy took on several different forms over the course of the pandemic (hence the term “dynamic”), but its aim remained consistent: To contain any outbreak of COVID and “zero out” new cases as quickly as possible without causing more disruption to people’s lives than necessary to accomplish that goal. The latter clause undoubtedly comes as a surprise to Westerners, because the stereotype is that China’s COVID policy revolved around lengthy lockdowns; even Anthony Fauci, who previously praised New Zealand back when it, too, pursued a zero-COVID policy, appears to share the misconception that China imposed draconian lockdowns throughout the country “without a seeming purpose.” But in fact, as of April 2022, only about 20% of the Chinese people had ever been locked down. And the most famous and longest of those lockdowns, the one in Wuhan where the pandemic began, only lasted a bit less than 2 1/2 months. In contrast, the UK locked down the entire country from January 6, 2021, to May 17, 2021 (with some limited easing in the month prior to May 17), just shy of 4 1/2 months.

Lockdowns were certainly an important part of China’s zero COVID approach. But dynamic zero-COVID did not revolve around lockdowns. Lockdowns were only imposed when public health officials deemed them necessary to control an outbreak, and targeted to very specific geographic regions such as a city or even a neighborhood. What distinguished lockdowns in China—and also in New Zealand—from those that took place in most Western countries is that they were enacted much sooner in the outbreak. As New Zealand’s Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern put it, locking down “early and hard” was the key to containing the initial COVID outbreak. The UK’s aforementioned lockdown succeeded in zeroing out COVID (until it did a 180 and abandoned all COVID mitigations), but because it started too late, it took over 4 months for it to contain COVID cases.

In any case, contrary to the impressions of Anthony Fauci and other Western observers, lockdowns were only one of many important ingredients of China’s successful COVID containment policy, and every aspect of its strategy had a purpose. Another key component of "dynamic zero COVID” was its massive testing and contact tracing program. A phone app that almost everyone had installed on their cell phones enabled public health officials to track who had recently tested positive for COVID and had traveled to high-risk areas or been in contact with others who had recently tested positive. Those who tested positive for COVID or reported COVID symptoms received a “red code” on the phone app, meaning they were not permitted to travel or visit certain locations; a “yellow code” meant that the individual had recently been in close proximity to someone who had tested positive, and was subject to certain restrictions; a “green code” meant that the individual had a recent negative test and had not recently been near someone who had tested positive, and was permitted to freely visit any public place where there was no outbreak, freely board mass transit, etc. Of course, this meant that, at least in large cities, everyone had to get tested frequently in order to maintain a green code. Foreign travelers had to undergo a lengthy quarantine (2-3 weeks early in the pandemic; later reduced to 1 week) prior to being able to enter the country, making tourism and business travel to China quite impractical. The rigorous quarantine (also imposed on Chinese residents who tested positive) meant that not only were relatively few if any people in a lockdown for long stretches of time, but life was actually relatively normal in most parts of the country—bars and restaurants were open, massive pool parties took place in Wuhan within weeks of the end of the early 2020 outbreak, and—ironically, unlike much of the US—schools were open in-person in fall of 2020. Of course, there continued to be occasional outbreaks, as it is difficult for even the most careful policies to keep such a contagious disease at bay indefinitely. But when they did, the response was swift and strict, and the vast majority were controlled within a month or less. In a recent video, I summarized China’s zero COVID policies and their success, and criticized the Western media’s relentlessly negative coverage of them.

The End of an Era: China Drops Zero COVID

But right after I made the video, China dropped its zero COVID policy, virtually overnight—and during winter, when COVID is most transmissible. There is no more mass testing of entire cities, you generally don’t have to show a “green” code indicating a negative test to go places any more, there are no more lockdowns, there’s no quarantine upon entry into the country (though negative test still required), etc. At the same time, wearing masks is still mandated in many public indoor spaces, people are still required to quarantine if sick, etc., so China hasn’t gone to the extreme of a vaccine-only COVID mitigation policy like most of the rest of the world. Nonetheless, the changes they have made have resulted in China going from having hardly any COVID infections most of the time to having countless millions of infections. Was this the right decision? In a video that my friend who lives in China, Jerry Grey, made recently, he said he thought it was, that China had picked the right time to open up.

But I must politely disagree with the view that this was the right decision—and I also question the official rationale for the decision. According to the Chinese Centers for Disease Control’s chief epidemiologist, Wu Zungyou, China made its policy changes after officials observed the worldwide number of weekly deaths to be below 10,000 for several weeks in a row. But that’s not what it looks like in the data I’ve seen. Rather, it appears from the graphic below, which shows average daily deaths (with a daily death rate of 1428 being equivalent to 10,000 weekly deaths), that the only time during the entire pandemic (aside from early 2020 when COVID had not yet spread worldwide) that the rate of weekly deaths fell below 10,000 was a couple of weeks in June 2022.

Throughout the fall, the worldwide number of deaths was above 10,000 the entire time. So I wonder what data he was looking at that led him to make this statement. It’s very puzzling. It seems in keeping with a general pattern I’ve seen in Chinese media stories about the pandemic, and on social media among people living in China, that the Omicron variant of COVID is not seen as very much of a public health threat compared to previous variants. The perception is that, particularly now that the country has achieved a high vaccination rate, Omicron is in effect “mild” and the impact of abandoning zero COVID in terms of the amount of severe illness will be minimal—that, basically, the primary outcome of giving up zero COVID will be life going “back to normal.” I’ve even seen some foreigners living in China saying things to the effect that Omicron is mild, like a cold.

I can state unequivocally based on closely following the outbreak over the past year or so since Omicron came on to the scene (as well as prior to that) that this perspective is simply wrong. In the United States where I live, more than 260,000 people lost their lives to COVID last year, and the overwhelming majority of those people were infected with the Omicron variant. Many other countries, such as Canada, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand, as well as the Chinese city/Special Administrative Region of Hong Kong, which is governed independently from the mainland and which had one of the worst COVID outbreaks of the entire pandemic last spring, have also had large numbers of severe illnesses and deaths as a result of this or that sub variant of the Omicron variant. And note that all of the countries mentioned above except the US have very high vaccination rates, and even the US has a very high rate among its elderly. Yet that did not stop Omicron from killing large numbers of people (despite it not inducing severe illness in the vast majority of those infected), even though death rates are far higher among the unvaccinated.

It appears that a lot of the optimism I’ve seen expressed within China about the likely impact of opening up on severe illness is based on observation of the outbreak in the city of Guangzhou during the fall. Basically, it’s been claimed that they were about 180,000 COVID infections in Guangzhou during its outbreak, and zero deaths. Now it may well be that there were no deaths during this outbreak, but it seems to be very much an anomaly for a city, state, or country with a massive outbreak of the Omicron variant of COVID, even though there is some evidence that acute illness from Omicron is not typically as severe as for some of the previous variants, such as the Delta variant. One thing that caught my eye in discussions of this outbreak is that it was said that about 90% of the infections were asymptomatic. Does that necessarily mean that we’re looking at a mild variant of COVID here? I don’t think so. For one thing, a significant majority of infections with previous variants have also been mild or asymptomatic. And in Guangzhou during this outbreak, the city pulled out all the stops to minimize the number of COVID infections. There was a lockdown, and more than half of the residents were given PCR tests for COVID. So, it’s likely that almost all of the COVID infections in the city were detected and that that detection occurred in a very timely manner. That is definitely not typical of how locales around the world have responded to COVID outbreaks; many, many cases are missed, or are not caught early enough to ward off severe illness. I don’t know enough about that outbreak to say for sure why there were so few severe illnesses, but those are a couple of plausible explanations.

At any rate, it seems questionable to assume that just because the outbreak in Guangzhou was so well contained that there were allegedly no deaths, that means that COVID has suddenly become milder than in the past. Although there were 180,000 positive tests during the Guangzhou outbreak, we’re probably looking at 1/10th that number who had symptomatic COVID, which is vastly less than the number of people who have been infected in places that haven’t gone to such great lengths to try to contain Omicron. And even within China, the experience of cities that have had significant Omicron outbreaks has never been that nobody died. At the beginning of 2022, official statistics indicated that there had been approximately 4600 deaths from COVID in China since late 2019. But during 2022, when Omicron has been the prevalent variant, there have been another 613 deaths. They were 333,389 confirmed cases, so that works out to a case fatality rate of .18%.

Now, imagine that if instead of 333,000 cases, there were 333 million. At the case fatality rate for 2022, that would be 613,000 deaths instead of 613. In fact, Wu Zunyou at the Chinese CDC estimated that around 10 to 30% of the Chinese population, or approximately 140 to 420 million people, would be infected with COVID this winter, and that between .09 and .16% of those infected would die. So, this puts the estimate of the number of deaths, according to Wu’s figures, at between 126,000 and 672,000.

The Unsurprising Result: 60,000 Deaths in 5 Weeks

Unfortunately for about 60,000 Chinese—and as presaged by this harrowing Shanghai Daily report on an overwhelmed Shanghai hospital—Dr. Wu’s prediction appears to be coming true. Reports are that in many parts of China, the majority of the population has now been infected with COVID, and the result has been that, according to China’s National Health Commission, there were 59,938 confirmed COVID-related deaths in China between December 8, 2022 and January 12 this year. That is more than 10 times as many people as died of COVID in China during the entire nearly 3-year period that China pursued zero COVID since the COVID pandemic began in Wuhan, China, in December 2019. According to Chinese public health officials, the number of hospitalizations peaked on January 5 at 128,000 (for comparison, the US, which has a bit under ¼ the population of China, had a peak hospitalization rate of about 150,000 people during its major Omicron wave a year ago). Based on statistics from other countries’ major waves, we should be seeing a peak in the number of deaths right about now. If that’s the case, then we can expect that by the time this wave is over, that 60,000 deaths will at least double. And note that Wu and other Chinese scientists are not expecting this wave to be the last one. Rather, Wu said, there will likely be other infection waves to follow this winter, with infections finally subsiding to a relatively low level by the end of winter.

So, it’s impossible to say what the final impact will be, but suffice it to say that this is going to be a rough winter in China with perhaps a couple hundred thousand deaths at least in mainland China, on top of who knows how many thousands of deaths in Hong Kong and Taiwan, which respectively have had about 13,000 and 16,000 deaths so far, as a result of their both having abandoned zero Covid almost a year before the mainland did. I have to wonder, what exactly is there to be gained here that is worth the unnecessary loss of hundreds of thousands of lives? To me, no amount of economic growth is worth such a sacrifice of lives (to say nothing of the suffering resulting from millions of non-fatal but severe acute illnesses and millions of cases of “long COVID”—long-term illness occurring after an individual no longer tests positive), and I suspect many people in China agree with me, even if most of them presently don’t see any alternative other than continuing with containment policies that have left a lot of people frustrated and a lot of businesses suffering. I’ll say more on what an alternative might be below, but first let me address some misconceptions many people have that lead them to underestimate the impact of COVID.

Some Common Misconceptions About COVID

One common misconception that a lot of people have about COVID is that, since the vast majority of people who die from it are older, COVID isn’t having much of an impact on overall deaths because most of the people who die from it would have died from something else soon anyway. But there are a couple of reasons why this view is incorrect. First of all, the number of people who die from COVID who are not elderly is far from trivial. About 20% of US COVID deaths in 2020 were in people under 65 (and pretty similar figure for 2021 and 2022). Given that the life expectancy prior to 2020 was about 78 (which is what it now is in China; the US's has declined), that's a lot of years of life that were lost for those people! Second, even older people aren't that likely to die in a given year otherwise. If someone has managed to make it to 80 years old without developing a terminal illness, their life expectancy is about 90, rather than 78 (since they already passed that). So in fact there are a lot of older people who would lose a lot of years of life if they were to die from COVID. A US study found that the estimated average number of years of life lost by people who died of COVID in 2020 was 14 years! In fact, it’s estimated that the US has lost 2.7 years in life expectancy over the course of the pandemic, having fallen behind China, where life expectancy is now 78 years, where is in the US it is now 76 years, the lowest it’s been since 1996.

Another misconception is the notion that if someone didn’t die solely because they had COVID (i.e., they had no comorbidities), that’s not a “real” COVID death. Of the 59,938 deaths Chinese health officials reported for the 5-week period starting December 8, 5503 deaths were reportedly due to respiratory failure, and 54,435 were reported to be due to “underlying conditions interacting with COVID infection.” But the notion that the latter are not truly COVID deaths reflects a misunderstanding of how deaths from diseases work. In fact, it’s quite typical when people are said to have died of this or that serious malady, such as cancer or heart disease, that they have other serious underlying conditions that contributed to their death. That doesn’t

mean that they didn’t really die from cancer, heart disease, diabetes, or whatever; rather, it just means that they likely wouldn’t have died had they not had both those primary conditions and the co-morbid ones. Had they only had the co-morbid conditions, they might very well have lived with those conditions quite a bit longer. As previously noted, the average person who has managed to make it to age 80 can expect to live approximately another 10 years. So even someone with several comorbidities likely won’t die that year without encountering a “straw that breaks the camel’s back” such as catching COVID.

A third misconception that many people have in the US and that I’m starting to see pop up in China as well is that we don’t have to worry about COVID any more once we’ve had it, that it’s a “one and done” sort of deal because getting COVID on top of being vaccinated, as people in China overwhelmingly are, is like getting another booster shot—and, relatedly, that between China’s extremely high rate of vaccination (91% fully vaccinated and about 60% with at least one booster shot) and the now extremely high number of people who have been infected with COVID, China is on the verge of “herd immunity” and being “back to normal.” This seems like a plausible assumption given the many diseases that were once scourges of humanity that are now very rare thanks largely to extensive global vaccination campaigns.

But before anyone starts partying like it’s 2019—that isn’t the way COVID works. The whole reason that we are where we are, three years into the pandemic and still with massive numbers of COVID infections worldwide, even in places like China with a more than 90% vaccination rate, is that the virus has evolved so that it can still infect people who have been vaccinated, even boosted, and/or have already had COVID. So if you believe mainland China will be out of the woods by the end of the winter, I encourage you to look at what’s happened in Hong Kong. After a massive outbreak

last spring that killed a huge number of Hong Kong’s largely at the time unvaccinated elderly population, the herd immunity notion would lead you to expect that between Hong Kong’s massively increased vaccination rate and the immunity conferred by its high infection rate last spring, that would protect it from having another wave. But it hasn’t worked out that way; Hong Kong has a very high infection rate right now, and as of the time I’m writing this, it has the highest death rate over the past couple of weeks of any major city in the world. Look how much higher its current death rate is than even the US’s. Omicron is extremely immune evasive. It’s been estimated that right now, almost 40% of infections in the UK are reinfections of people who have already had COVID before. And reinfections can be very problematic. The study whose results are depicted below showed a greatly increased risk of a wide variety

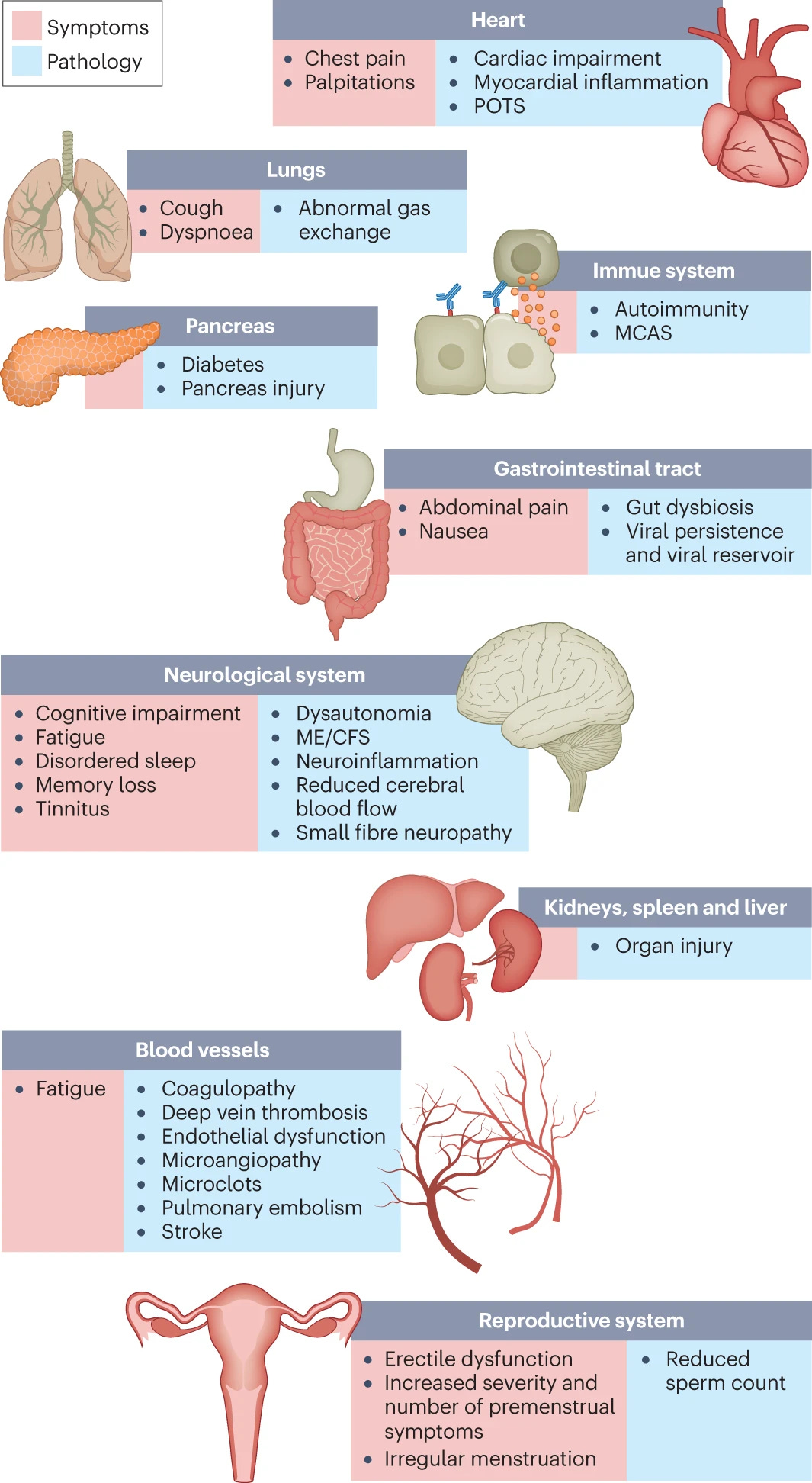

of health problems following COVID reinfections. Granted, this study examined an older population, but COVID is a vascular (not just respiratory) disease that can cause bodily damage throughout the body, so there is no reason to believe that there is not some degree of increased health risks following reinfection for younger people—not to mention that the first infection is hardly risk-free even for young people. In fact, a recent study published in the Journal of Medical Virology found that deaths from heart attacks have increased significantly in all age groups, and that increases have tracked with spikes in COVID (including Omicron) infection rates. In short, the health crisis associated with COVID will not simply disappear once China makes it through the winter.

Surviving COVID Is Only Half The Battle

Of course, the overwhelming majority of China’s 1.4 billion people will survive being infected with COVID. But, as the study cited above on the risks of reinfection makes clear, the damage the SARS-CoV-2 virus can do isn’t limited to killing people. Here in the US, in addition to over 1.1 million deaths (that we know of), we’ve had millions of people hospitalized with serious illness. Over 200,000 American kids have lost a parent, or sometimes both parents, to COVID. Even more common than severe acute illness with COVID is long COVID (also known as post-COVID syndrome), a syndrome comprising often severe symptoms that either continue after or begin following the typical recovery period for a COVID infection which can last months or even years after one is initially infected. The figure below shows some of the symptoms and bodily damage that can occur. It has been conservatively estimated

to have occurred in about 10% of COVID cases overall, including 10-30% of non-hospitalized individuals, 50-70% of hospitalized individuals, and 10-12% of vaccinated individuals. Thus, given the current number of 670 million confirmed infections worldwide, at least 67 million people have likely developed long COVID thus far, and of course 670 million is a considerable underestimate of the actual number of infections. Indeed, reports suggest that there have now probably been more than that number of COVID infections in China.

To be sure, there is some research suggesting that, even after adjusting for the fact that more of the world’s people are vaccinated during the Omicron era than was the case with previous variants, Omicron appears somewhat less likely to cause severe illness, including long COVID. A recent study found that it was approximately half as likely as the Delta variant to cause long COVID (4.5% of those infected with the Omicron variant vs. 10.8% of those infected with the Delta variant developed long COVID).

But even if “only” about 5% of those infected with an Omicron version of SARS-CoV-2 go on to develop long COVID, that still adds up to an enormous number of people. Let’s suppose, just to choose a random round figure, that 700 million people in China get infected with COVID this winter. 5% of that is 35 million people who are afflicted with debilitating, health-damaging aftereffects of COVID for at least several months. Some of those people will be too incapacitated to work, attend school, etc.—an estimated 2-4 million Americans are at any given time (and often indefinitely) unable to work due to long COVID.

Thus, in multiple respects, this pandemic is damaging our lives, and not making a concerted effort to limit the number of people who are infected with COVID multiplies that damage. Now, I can certainly understand that after three years, people in China have gotten very tired of lockdowns if they experienced them (though the majority of Chinese citizens haven’t) and tired of having to show a green code on their phone app to go places. The overwhelming popular support for strict measures to contain COVID that existed in 2020 has undoubtedly declined, and although China has fared vastly better economically during the pandemic than most countries, it is also hard to argue that in those places where lockdowns occurred, businesses such as bars and restaurants that depended on in-person traffic for much of their income have not suffered during the pandemic. And given that most of the rest of the world, including some of China’s own autonomously governed regions, abandoned serious efforts to contain COVID infections long before mainland China did, it is understandable if many people in China see it as having to make a difficult choice between itself abandoning most efforts to contain COVID infections and indefinitely maintaining policies that, though they can still prevent a lot of illness, cause a great deal of inconvenience and hamper economic development (uncharacteristically, China’s economic growth rate was only 3% in 2022).

Thinking Outside the Box: How China Could Have Its Cake and Eat It Too

With apologies to those who are not very familiar with English language idioms and might be irritated by my using two in one heading, a case can be made that there is a third choice that can minimize both COVID infections and limitations on social and economic life. To see how that might work, think back to when waterborne diseases such as cholera and polio were commonplace throughout the world. What was the problem? The problem was that the water was full of viruses, bacteria, protozoa, etc. that made people sick. What was the primary solution? Cleaning up the water! To be sure, other measures, such as antibiotics, vaccines, hand-washing, etc. are also very important for controlling some of these diseases, but reliable access to clean drinking water, typically requiring treatment of existing water supplies, is the core of preventing them (and unfortunately is still lacking in some poorer parts of the world).

Analogously, the primary problem with airborne infectious diseases such as COVID is the prevalence of dirty (virus-filled) indoor air! The overwhelming majority of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 occurs in public indoor spaces where, when there is high community transmission, it is highly likely that sooner or later one will encounter an infected person—or, rather, encounter air contaminated by infected people. That is far less likely outdoors, where viruses are quickly dispersed, or in our own homes (except in cases of apartments with shared hallways), where there are far fewer people than there are in a grocery store, on a train, etc. Thus, arguably the most important task ahead of us in finally bringing an end to this pandemic (and no, Joe Biden, it is not over yet!) is to clean indoor air.

There are several ways to do this. One is to improve buildings’ ventilation. Unfortunately, the cheapest way to do so—opening windows—is not practical during cold or extremely hot weather. Redesigning buildings’ ventilation systems to bring in more outdoor air requires a significant investment. But government investment in improving building ventilation—like investment in improving insulation in order to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and heating and cooling costs—would have a big payoff in the long run in terms of reduced incidence of airborne infectious diseases, and it should be a priority for governments worldwide.

Another, relatively affordable, approach is air filtration. I recently purchased a HEPA (high-efficiency particulate absorbing) air filter for $90 US for my girlfriend, who’s been complaining of bad headaches lately, most likely due to some mold or other allergen in the air, and she’s had no headaches since we set up the air filter, which is also extremely effective at filtering out viruses. A cheaper alternative than commercial air filters (which are more costly than this for a large room) that may be even better for filtering the air is what’s known as a Corsi-Rosenthal box, which is basically a homemade device consisting simply of a box fan, four HEPA 13 furnace filters, and some cardboard for the base, as well as some duct tape to hold everything together. The estimated cost is under $100 US. So, if you can afford to purchase or build an air filter, I would highly recommend it, especially if you live in an apartment with a common hallway, or if you have guests or repair personnel over, and you don’t know for sure what their infection status is. (You could also, of course, ask them to wear a mask.)

An even more effective, although more expensive, alternative is far-UV light, which directly kills a large quantity of viruses. However, far-UV lamps typically cost several hundred US dollars.

Perhaps you’ve heard that the World Economic Forum, the annual “rich people and politicians plot to further their world domination” event in Davos, Switzerland, is going on right now. The meeting rooms all have air filters, and reportedly UV lights as well—and the WEF is well aware of the virus-killing benefits of UV light. In addition, all attendees are required to take a COVID PCR test upon arrival—and if they test positive, they are not allowed to attend. So, it appears that many in the world’s power elite are well aware that it’s a good idea to try to avoid getting COVID, and have taken steps at their conference to reduce their odds. Meanwhile, essentially all of their countries’ governments have all but abandoned infection mitigation efforts. I guess that for WEF attendees, control of airborne infectious diseases is “for me and not for thee.”

At any rate, my point is that we have a panoply of measures available to us to mitigate the spread and impact of COVID, and we need to employ a wide range of them. We need not employ all of them in order to continue pulling off the feat of keeping COVID infections in check, as China was doing before it “optimized” its COVID measures over the past couple of months. But clearly, even near-universal mask-wearing and vaccination will not suffice by themselves—as China’s recent massive wave demonstrates. There are several reasons for this. First, the vaccinations, particularly if they are not recent and/or people have not had booster shots, strongly protect against severe illness but do much less to protect against Omicron infection. We may eventually have vaccines that do a better job of protecting against infection and transmission, but we cannot count on it—and even less so if there remain people who are unvaccinated or not recently vaccinated. Second, most people wearing any old mask most of the time in public is not good enough to maximize the efficacy of mask-wearing as an infection control measure. Masks differ widely in quality. The higher-quality ones, known as N-95 or P-100 masks in the US, perform extraordinarily well at preventing infections if everyone in a space is wearing them. A recent study found that under the circumstance where a non-infected person is exposed to an infected person for about 20 minutes, when both people are wearing FFP2 masks (the German equivalent of N-95s), the rate of infection is estimated at about 1000 times lower than if neither party is wearing a mask (when it’s close to 100% likely that infection will occur during that time frame). And people are unlikely to give up things like eating in restaurants or on public transit unless the government tells them they can’t.

So, we must do more than just getting vaccinated and wearing masks in public places, and doing all that is necessary will require the same level of government investment in and attention to public health that China has shown for the past 3 years (and not just in China, but everywhere in the world that can afford it). Reining in the COVID pandemic will not happen with individual action alone; it will require massive governmental investment in cleaning indoor air, just as China has invested so heavily in the development of high-speed rail and renewable energy over the past 10 years. But the payoff will be worth it: An end to the COVID pandemic, massive reductions in rates of other airborne infectious diseases (which, worldwide, kill 4 million people a year), a head start in combating future disease epidemics, and a healthier, freer, and more prosperous society.