How Infectious Diseases—and Conspiracy Theories—"Go Viral"

As Scientists Accumulate Evidence for the Zoonotic Origin of COVID-19, Anti-China Hawks and Conspiracy Theorists Double Down on the Lab Leak Theory

How Lab Leak Theory “Went Viral”

Origins: Lab Leak Theory as a Far Right Conspiracy Theory

In November, 2002, a deadly viral illness called SARS broke out in Guangdong province in southern China. Although considerably more likely to be fatal than COVID-19, with a case fatality rate in the neighborhood of 10% as opposed to COVID-19’s approximately 1% CFR for confirmed cases, SARS proved to be far less contagious, and ultimately caused only 8,000 known cases and fewer than 800 deaths. Like the vast majority of epidemics, SARS ultimately was traced to a zoonotic origin; that is, it resulted from the virus jumping from animals to humans. The initial outbreak was traced to wild animals sold at an animal market in Guangdong, China, and many years later, virus species comprising the building blocks of SARS were found in horseshoe bats living in caves in Yunnan province, hundreds of miles away. History appeared to repeat itself in late 2019 in Wuhan: A mysterious pneumonia outbreak occurred. One study identified 41 people who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 (then known as 2019-nCoV) as of Jan. 2, 2020, 27 of whom had direct exposure to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market (where wild animals had been illegally sold for years) either as employees or as visitors.

Yet, from the very beginning, the Trump administration and its allies in Congress and the far-right corporate media promoted the claim that the COVID pandemic came about through a leak from the Wuhan Institute of Virology lab rather than the Huanan market, where the first known cases had appeared. On January 24, 2020, the Washington Times, a newspaper owned by the Unification Church cult (more popularly known as the “Moonies”), proclaimed that “Coronavirus may have originated in a lab linked to China’s biowarfare program.” Radio Free Asia, a CIA-created US propaganda outlet, made similar claims.

For a few months, lab leak theory remained on the fringes of public discourse. But in April, discussion of it began to be revived in earnest. Neoconservative Washington Post columnist Josh Rogin, Republican Senator Tom Cotton, Fox News’ Brett Baier, former White House official Steve Bannon, and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, among others (including of course Donald Trump), elevated the theory to national prominence. At the time, a poll found that 30% of Americans thought the COVID pandemic had come about due to a lab leak, despite no evidence that it had. Nonetheless, for a long time, the notion that China had either manufactured and released SARS-CoV-2 as a bioweapon or that it had leaked from the lab by accident, and thereby led to the COVID pandemic, largely remained the province of the far right, with more liberal mainstream media outlets tending to dismiss it as a Trumpian conspiracy theory.

Lab Leak Theory Goes Mainstream

But the lab leak theory was never entirely the province of the far right, and in early 2021 it began to go mainstream, first with a Feb. 5 Washington Post editorial entitled “We’re still missing the origin story of this pandemic. China is sitting on the answers,” followed by a Feb. 22 Post editorial entitled “The US should reveal its intelligence about the Wuhan laboratory.” Shortly thereafter, Facebook began censoring critics of the Post’s editorial, claiming that they were purveying “false information that has been repeatedly debunked.”

A USA Today editorial that had flatly declared in March 2020 that “Overwhelming scientific evidence suggests the coronavirus originated in nature, and there is no evidence to suggest otherwise” was revised in February 2021, changing its rating of the claim that the virus originated in a lab from “false” to “partly false,” and maintaining that although experts agreed that the virus originated in nature and was not deliberately engineered, “circumstantial evidence such as the Wuhan Institute of Virology's history of studying coronaviruses in bats, the lab's proximity to where some of the infections were first diagnosed and China's lax safety record in its labs” made an accidental escape from the lab a plausible scenario. No evidence was presented that China had a lax safety record in its virology labs, “proximity” only means “in the same city” since the WIV lab is located about 12 miles away from the Huanan market where the first cases were detected, and the fact that the WIV was studying bat coronaviruses means little since coronaviruses are very genetically diverse and the closest relative that had been identified at the time the pandemic began was RaTG13. RaTG13 was found in an early 2020 study to differ from SARS-CoV-2 by about 4%, which percentage-wise is a larger genetic difference than there is between, say, pigs and humans. It is particularly different in terms of the crucial receptor binding domain, which means it is unlikely to be able to infect humans.

So, what evidence prompted this change from “false” to “partly false”? Literally none. The revised fact-check informs the reader that two Biden administration officials, speaking on condition of anonymity, told USA Today that “they have always questioned China's account of how the virus originated and have taken seriously suggestions that it may have resulted from a lab accident that the Chinese are covering up”—in short, speculation by anonymous government officials that fits right into the “China bad” narrative the US establishment has been promoting for years is the reason why USA Today revised its fact check.

A further foray into rehabilitating the credibility of the lab leak theory with those who previously rejected it because of its association with Trump et al. was a Wall Street Journal column by Michael Gordon, Warren Strobel, and Drew Hinshaw. Like the USA Today’s revised editorial, the column cited anonymous government officials’ claims as the “evidence” for its contention that a lab leak was plausible. Essentially, their claim was that three researchers from the Wuhan Institute of Virology had supposedly “become sick enough in November 2019 that they sought hospital care,” with “symptoms consistent with both Covid-19 and common seasonal illness.” No evidence was ever presented by the Journal or the US government that this actually occurred—no hospital records, no names of the supposed patients, no information verifying what illness they might have had if any, nothing. For all we know, it could be another claim along the lines of “Iraq has weapons of mass destruction.” Funnily enough, Michael Gordon is the same journalist who in 2002, along with Judith Miller, wrote a New York Times piece claiming that Iraq had “weapons of mass destruction.” That one article arguably did more than any other to convince the majority of the public that this was true.

Granted, the WSJ column did not report the claim about the sick workers as a verified fact, and asked COVID origin researchers what they thought about COVID’s origins. However, neither did they significantly challenge the claim, and other media outlets (e.g., CNN) reported it as a fact. Moreover, a significant fact about the Chinese medical system went unreported: Hospitals are a common site for routine medical care in China. Thus, assuming there were indeed three employees at the Wuhan lab who sought treatment at a local hospital for a respiratory illness, it is not necessarily the case that it was a serious illness. After all, it was cold and flu season at the time. A further piece of information not mentioned by Gordon and his colleagues is that all staff were tested for COVID-19 antibodies in early 2020, according to Shi Zheng-Li, director of the Center for Emerging Infectious Diseases at the WIV, and none tested positive. (Dr. Shi also happens to have been the leader of the team of researchers who discovered the origins of the SARS virus in 2017, and among the developers of a PCR test for COVID.) Unsurprisingly, news reports have tended to assume or imply that Dr. Shi is lying about this; however, there is no evidence to suggest that this is the case.

Another reason why, according to Glenn Kessler of the Washington Post, the lab leak theory had “suddenly become credible” is that in mid-May, 18 prominent scientists published a letter in the journal Science maintaining that it was important to continue giving serious consideration to both the lab leak and zoonotic origin theories until evidence for one or the other became sufficiently overwhelming. However, what Kessler fails to understand is that they were merely stating what any scientist would: Until a given hypothesis is contradicted by a large body of evidence, it remains a possibility worth considering. But “possible” does not necessarily mean “likely”; the vast majority of past human disease outbreaks, including SARS-CoV-2’s closest epidemic-causing relative, SARS, have resulted from zoonotic spillover. Several of the signers of the letter have subsequently pointed this out, and explicitly stated that they considered the lab leak hypothesis implausible even though it could not be ruled out. (More on why they considered it implausible later.)

Another event cited by Kessler as supposedly making the lab leak theory “suddenly credible” was a May 5 Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists column by science journalist Nicholas Wade. Kessler claimed that Wade’s article “makes a strong case” for the lab leak theory. But did it really?

Wade makes much of the fact that the Wuhan Institute of Virology is located in the same city where the first major outbreak occurred, and of the fact that the outbreak occurred hundreds of miles away from the part of China, Yunnan province, where bats who harbor coronaviruses highly similar to SARS-CoV-1 were found. However, first of all, Wuhan is a very large city, containing not just a virology lab but the same sort of animal “wet markets” that were conclusively shown to be the source of the 2002 SARS outbreak. And many of the initial cases were associated with workers at, or visitors to, the Huanan market, whereas none were detected among employees at the Wuhan Institute of Virology. As for the fact that Wuhan is not located near the region where coronavirus-harboring bats are most prevalent (and presumed to be the origin of SARS-CoV-1), as virologist Kristian Andersen, co-author of one of the papers on COVID’s origins I will review below put it, the city where SARS initially broke out was actually about the same distance away. And we don’t know for sure where either SARS virus originated, because Yunnan province is hardly the only area where horseshoe bats, the type of bats that most commonly harbor SARS-related coronviruses, live.

The kicker, Andersen goes on to point out, is that more animals were found to be infected with SARS-CoV-1 on farms in Hubei province, where Wuhan is located, than in any other province in China. Moreover, farms in Hubei province supplied animals to wet markets in both Guangdong province and Wuhan.

Wade also makes much of the fact that, whereas the intermediate animal hosts (species infected by bats that were likely responsible for transmission to humans) for SARS-CoV-1 were found in 4 months, and for the MERS virus in 9 months, no intermediate host for SARS-CoV-2 was found by May 2021 when Wade wrote his article. However, Wade fails to note a crucial difference between the three situations: the Chinese government reacted almost immediately to SARS-CoV-2, closing down Wuhan’s animal markets within about a week of the first detected cases with a known connection to the Huanan market and testing all the animals that were there. Although no animals tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, no animals known to be carriers of coronaviruses (palm civets, raccoon dogs, etc.) were found when the market was closed down, even though they were determined to have been sold there through late 2019. A plausible explanation is that wild animal traders, knowing that their selling wild animals at the market was a felony and likely also knowing they had animals in their possession that could carry coronaviruses, removed these animals from their market stalls before government officials arrived.

Wade gives the misleading impression that it’s a fast, easy process to track down the origins of a viral outbreak, when that’s far from the case. Although with SARS and MERS researchers got a lucky break in tracking down intermediate hosts because of “data preservation” (i.e., the animals were still around months later), it took 15 years to track down the likely bat origins of SARS-CoV-1, and even then they did not find that virus per se, but numerous close relatives that likely could have combined to produce it. And although the evidence strongly supports their having had a zoonotic origin, the precise origins of several coronaviruses and other viruses that spilled over into humans (e.g., Ebola and hepatitis C) are unclear. Given that animals known to host SARS-CoV-2, although known to be present at the Huanan market in late 2019, were not found at the market when it was shut down and animals present were tested, it is not possible for direct evidence regarding the intermediate host(s) that precipitated the outbreak to be found. And although fairly close relatives of SARS-CoV-2—closer than any relative present in virology labs at the time the pandemic began—have been found in the wild, it is anyone’s guess how much progress scientists will be able to make in finding enough SARS-CoV-2-like viruses in the wild that we can (as with SARS-CoV-1) claim to have found the viral building blocks with which SARS-CoV-2 could have evolved, or how long that research process will take.

Wade’s “smoking gun” that the virus was supposedly genetically engineered in a lab rather than birthed from nature like SARS-CoV-1 and other coronaviruses is the existence of a furin cleavage site, a feature of some coronavirus’ structure associated with cleavage of spike proteins by furin (an enzyme) that facilitates its ability to enter cells. Wade makes a big deal of the fact that of the SARS-related coronaviruses, only SARS-CoV-2 has a furin cleavage site, while ignoring that it is a common feature of coronaviruses generally, and is far from optimally designed for serving its function. (For further information/details on how Wade gets the science wrong, see here and here.)

Many corporate media outlets have accorded Wade a great deal of credibility. But they fail to mention that not only is Wade not a scientist of any sort (he has an undergraduate degree in biology), he also has a track record of promoting racist pseudoscience, in the form of a 2014 book that purported to show that there were genetic differences between “races” in intelligence. Never mind that it has been long-established that there is no such thing as “genetic race,” even though obviously there are genetic factors that influence skin pigmentation and other aspects of physical appearance. In short, Wade is not someone whose views about complex scientific matters should ever have been taken seriously, but it is unsurprising that the mainstream media, which is generally superficial in its coverage of scientific issues—especially when, as in this case, there are political motives involved—failed to analyze his claims critically. To its credit, the “liberal” wing of the corporate media gave scientists with expertise on viral origins, such as virologists Angie Rasmussen and Stephen Goldstein, space to expound on the issue, and the views expressed in these media were generally not as monolithic as those in right-wing media. Nonetheless, the propaganda offensive was sufficient to result in a majority of the public surveyed (52% vs. 29% in March 2020) subscribing to the lab leak theory in July 2021, despite no real evidence to support it. That’s what tends to happen when unsubstantiated claims are repeated over and over. Remember “weapons of mass destruction”?

Independent and “Left-Wing” Media Push the Lab Leak Theory

Even some left-leaning or populist journalists or public figures with no connection to mainstream media, who portray themselves as “anti-establishment,” bought into the lab leak theory. Jimmy Dore, Russell Brand, Jon Stewart, Glenn Greenwald, Zac and Gavin from The Vanguard, and several commentators currently or formerly associated with The Hill’s political commentary show Rising, such as Krystal Ball, Saagar Enjeti, Kim Iversen, and Ryan Grim have insisted on the veracity or at least credibility of the lab leak theory. Greenwald even praised neoconservative Washington Post columnist Josh Rogin for his dogged persistence in pushing the theory during the time when most of the media were dismissing it as a Trumpian conspiracy theory. The Hill’s Rising show has been particularly obsessed with the topic, literally doing dozens of segments on it in the past couple of years—and never once interviewed any scientists who have conducted research on COVID’s origins. Why would some independent journalists promote the same views as many of those in the mainstream media? There are various reasons. Like their corporate media counterparts, they typically have little to no scientific background, and do not give the appearance of having read scientific journal articles regarding research on COVID’s origins. Some are China-bashers like the corporate media and US political elites generally are. And generally, they share the same disdain for the “liberal media” that the right-wing mainstream media have, although they refer to it in different terms, such as “establishment media” or “corporate media,” while often ignoring that Fox News, the Washington Times, the Wall Street Journal, etc. are equally part of the corporate media. Finally, as with the mainstream media, the financial benefits of promoting a “juicy” story concomitant with viewers’ biases may be too much to pass up. In short, for a variety of reasons, dispassionate examination of the evidence takes a back seat to the narrative that “they” are up to no good, and that seat is all the way in the back of the bus. What does that evidence say? Let’s take a deeper look.

The Origins of COVID: What Does the Evidence Suggest?

Since very early in the pandemic, most scientists with relevant expertise—although they have not dismissed the lab leak hypothesis out of hand, because scientists don’t discard hypotheses before they have evidence—have leaned strongly toward the view that the COVID pandemic had a zoonotic origin, and toward the view that the most likely place where it originated was the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan, China. As time has gone on, evidence has steadily accumulated that favors that hypothesis. Kristian Andersen, a virologist at Scripps Research and co-author of several studies on COVID’s possible origins, summarizes the reasons why the evidence supports this hypothesis here, and elaborates on them in a clearly explained Twitter thread. Here, I will discuss some of the points Kristian makes, and a few other details pertaining to the body of evidence regarding COVID origins.

The main reason why zoonosis, and spread from an animal market, has overwhelmingly been regarded by scientists with relevant expertise as the most likely origin is simple: Precedent. The trajectory of COVID’s emergence looks very much like SARS. In both cases a large proportion of the initial cases were associated with an animal market, in November, in a major population center (where, thus, there were many potential targets of infection). And although the animal species identified as hosts of SARS-CoV-1 were not available to be tested for SARS-CoV-2 when the Chinese government closed down the Huanan market on Jan. 1, 2020, they were present at the market in late 2019. Moreover, all of the other coronaviruses that have infected humans (SARS-CoV-1, MERS-CoV, etc.) have been shown to have emerged zoonotically.

There are thought to be millions of different species of viruses, most of them as of yet undiscovered. Within that massive morass of viruses, several species have been identified that are relatively similar to SARS-CoV-2. The first such species, as noted earlier, was RaTG13 (discovered in 2013), which was determined in February 2020 to be approximately 96.1% the same genetically as SARS-CoV-2. (Bat virus experts have estimated that, assuming RaTG13 and SARS-CoV-2 came from a common ancestor, they diverged approximately 40 to 70 years ago.) This is a close-but-no-cigar degree of genetic similarity, with less genetic similarity, percentage-wise, than there is between humans and pigs (98%) and much less than between humans and their closest relatives, chimpanzees. Since then, several other viruses have been discovered that resemble SARS-CoV-2, including three viruses (BANAL-52, BANAL-103, and BANAL-236) that, while not substantially more similar to SARS-CoV-2 overall (BANAL-52 has 96.8% similarity), are extremely similar in the receptor binding domain, and thus are believed to be capable of infecting humans. Although there is much research yet to be done in order to build a case as strong as that for SARS-CoV-1 that the building blocks for the evolution of SARS-CoV-2 exist in nature, it’s likely that someday that will be accomplished. In the meantime, these findings are strongly suggestive of a zoonotic origin.

An important piece of context that Andersen discusses is that horseshoe bats, the animals most noted for harboring SARS-producing coronaviruses, live throughout southeast Asia—including in Hubei province—so it shouldn’t be automatically assumed that SARS-CoV-2’s (or even SARS-CoV-1’s) spillover from bats to other species took place in Yunnan province. In fact, the three close relatives that were mentioned above were found in bat caves in Laos. Theoretically, the intermediate host animals that likely brought SARS-CoV-1, SARS-CoV-2, or both to the human population could have lived in a variety of places, including on farms in Hubei province, where the largest share of SARS-CoV-1-infected animals were found during the SARS epidemic.

I have previously discussed the fact that numerous coronaviruses have been found in the wild in the past two years that have important similarities to SARS-CoV-2, including in the receptor binding domain, crucial to human infectiousness. At the same time, the original “wild” virus (which came in two forms, Lineage A and Lineage B) was neither as optimally designed for infecting humans as variants that came along later nor was it designed to specifically infect humans. It has been shown to have infected mink, tigers, cats, gorillas, dogs, raccoon dogs, and ferrets, and there have been documented spillover events from humans to mink and back again. And as noted above, animals susceptible to coronavirus infections, including raccoon dogs (animals that tested positive for SARS-CoV-1 in Guangdong markets during the SARS outbreak), civet cats, foxes, and mink, were being sold at the Huanan market in late 2019—and had been sold there for several years prior to that.

A very large percentage of the early cases had some connection to animal markets. I previously mentioned that 27 of 41 identified early cases (66%) either worked at or had visited the Huanan market. Importantly, cases were identified on the basis of symptomatology (and eventually by PCR test), not whether they had been to that or any other animal market. A later World Health Organization report found that 55 of 168 early cases (33%) were associated with the market. More than half (93 of 168) had exposure to one or more animal markets.

Two July 2022 papers published in Science add greatly to the body of evidence suggesting that the Huanan market was crucial to the pandemic’s origin. Worobey et al. collected a variety of evidence showing that, as they put it, the Huanan market was the early epicenter of the pandemic.

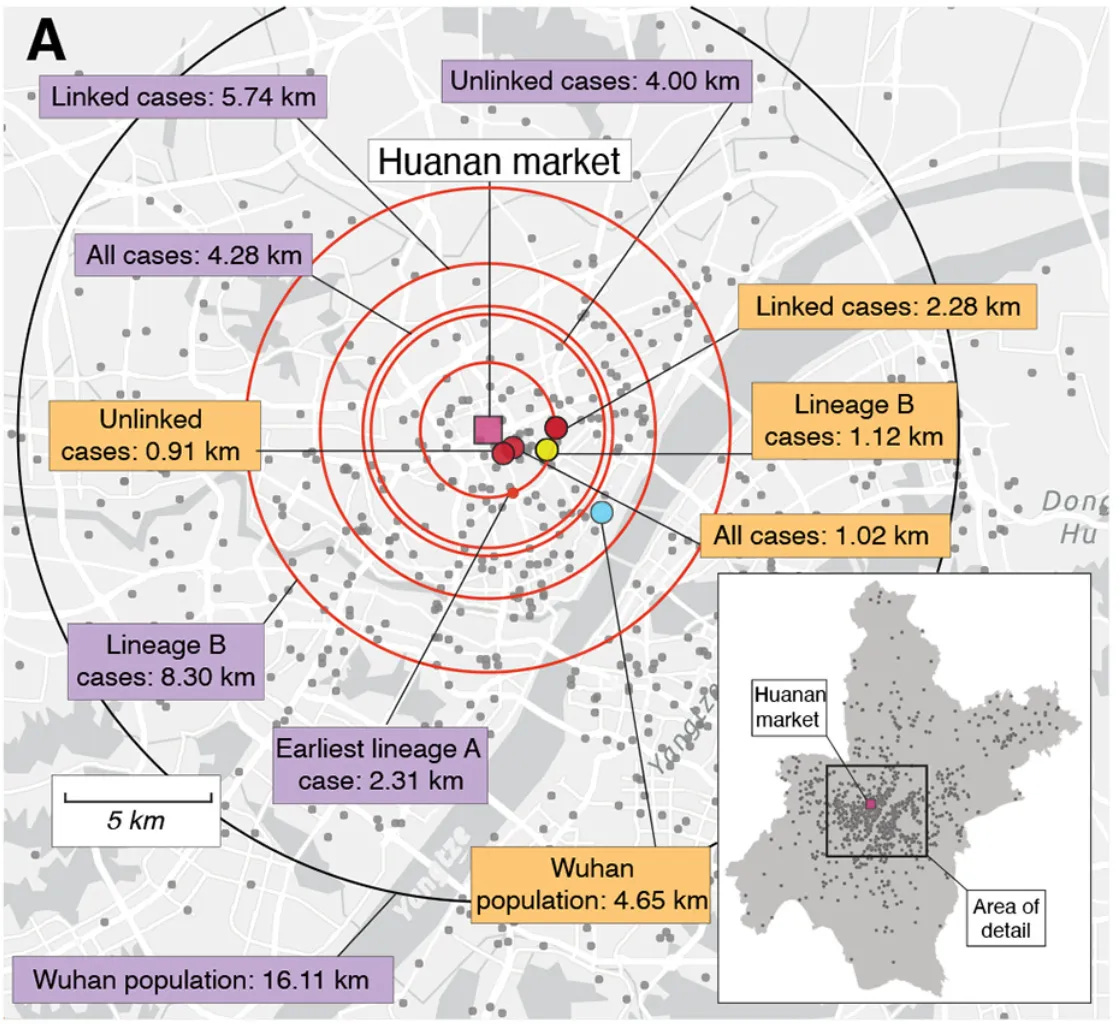

First, the researchers were able to obtain information about where in Wuhan—a very large city of 11 million—155 of the early cases lived, and showed that by far the highest density of cases was in areas near the west bank of the Yangtze River in central Wuhan—the location of the Huanan market. Whereas the average Wuhan resident lived 16.11 km from the Huanan market, the average Wuhan resident identified as infected with COVID among these early (2019) cases lived only 4.28 km away. And, whereas the average infected individual with a connection to the market (worker or shopper) lived 5.74 km away from it, the average infected individual with no known connection to the market lived only 4 km away. As you might imagine, for all three of these numbers, the researchers found that the probability of their being that much smaller than 16.11 just by chance was extraordinarily low, less than 1 in 1000 (p < .001). Also, the infected individuals who were unconnected to the market lived significantly (p < .03) closer to the market than those who had been in the market; this suggests that infected individuals who worked or shopped at the market infected people living in the neighborhoods surrounding the market through visiting restaurants, shops, etc., and it then spread in those neighborhoods.

It gets even better. When the center point of all 155 cases was plotted, it was only 1.02 km from the market! For cases linked to the market, the center point was 2.28 km away, and for cases not linked to the market, the center point was only .91 km away. (For users of English measurements such as myself, that’s less than 3000 feet.) Compare that to the average distance away from Huanan that Wuhan residents lived (16.11 km), or the distance between the market and the center of Wuhan’s population distribution (4.65 km), and it is apparent that these are quite amazing results. Someone who was playing darts with a dartboard where the Huanan market was the bullseye of a map of Wuhan would have to be extremely good to get this close! Or, to put it in mathematical terms, there is less than a 1 in 100,000 chance that the area immediately surrounding the market would have a case density that large relative to the rest of Wuhan just by chance. Moreover, as one would expect, Wuhan cases from January-February for which the authors had location information lived much farther away from the Huanan market on average than the early cases, with an average distance of 5.24 km from the market.

Pekar et al. established that there were likely at least two separate spillover events from animals to humans that occurred in the Huanan market, roughly a week apart, involving the two lineages of early SARS-CoV-2. Lineage B, the one that ultimately led to the pandemic, was estimated by the authors to have spilled over around mid-November, and Lineage A in late November. Worobey et al. established that both of these lineages were strongly geographically associated with the market.

Furthermore, Worobey et al. observed, numerous other public places in Wuhan received much heavier visitor traffic than the Huanan market. According to data collected from the Chinese social media site Weibo, there were more than 400 locations in Wuhan that people reported visiting more often than people reported visiting the Huanan market—other markets (live animal or otherwise), malls, hospitals, places of worship, universities, etc. Yet none of these other locations had even remotely close to the number of early (2019) reported cases associated with them that the Huanan market did. Hence, the Huanan market was not just another superspreader event; all indications are that it was the original superspreader event, the one that initiated the pandemic.

Finally, they present data regarding exactly where in the market environmental samples testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 were found, as well as data regarding what part of the market a few of the infected individuals who were known to have been in the market had worked in or visited. Positive environmental samples were highly likely (p < .05) to be located in the southwest corner of the market, where live animals were sold, and all eight of the infected individuals who were known to have been in specific parts of the market had been on its west side.

The body of evidence in general, and that presented in the two Science papers in particular, utterly demolish the credibility of the lab leak hypothesis. For it to be true, there would need to be not just a lab worker infected at the Wuhan Institute of Virology traveling the 19 km from there to the Huanan market, spreading the disease to workers and shoppers specifically at the market (and disproportionately on the west side of the market where live animals were sold) and barely anywhere else, but at least two lab workers, infected with two different variants of SARS-CoV-2, visiting the market a week apart and infecting people, disproportionately on the west side, while hardly infecting anyone in the hundreds of other locations with much heavier visitor traffic. I don’t know about you, but I’m a believer in Occam’s Razor, and the difference in parsimony between the zoonotic origin and lab leak hypotheses given this body of evidence is colossal.

Furthermore, even in the absence of any evidence, subscribing to the lab leak theory requires one to believe (without evidence) that Chinese scientists are lying and covering things up (or, in the “it came from an American lab” version of the lab leak conspiracy theory, that American scientists are lying). As a scientist myself, I take umbrage at the idea that Chinese scientists should not even be given the benefit of the doubt, particularly given that there is considerable evidence supporting zoonotic origin (and specifically spillover at the Huanan market) and there is no evidence that there was a lab leak and a subsequent conspiracy to cover it up. Be that as it may, the fact of the matter is that media with a wide variety of political perspectives have promoted the lab leak theory, and as of July 2021, a poll showed that the majority of Americans believed in the lab leak theory. That begs the question: Why?

If the Evidence Supports Zoonotic Origin, Why Do So Many Believe the Lab Leak Theory?

At this point, as you’ve just read, there’s very strong evidence that the pandemic began at the Huanan market and perhaps to a lesser extent at other wet markets in Wuhan, and none that it was initiated by a deliberate or accidental lab leak. And yet, 52% of Americans according to a poll from a year ago believe that COVID began with a lab leak, and journalists representing both far-right and liberal corporate media as well as some from independent left or libertarian media have strongly promoted the lab leak notion. I’ve already briefly discussed some reasons why this discrepancy between the views commonly promoted or subscribed to and what the scientific evidence suggests is true, but in closing I’d like to take a bit of a deeper dive.

First, the political context of the obsessive promotion of the lab leak theory by the US corporate media and many politicians is that we are in a New Cold War. Since China and Russia have been rising economically to such an extent over the past couple of decades, they (particularly China, which is a vastly larger country than the US and will soon become the biggest economy in the world) have become a challenge to US hegemony in the world. In response, both the Republican and Democratic wings of the US elite have launched a propaganda campaign to declare everything about China and Russia bad (and some populist independent media figures, such as Saagar Enjeti and Ryan Grim, gladly join in the fun, at least with regard to China). In the context of COVID, this has meant an attempt to blame China for the pandemic by claiming that the Chinese government and Chinese scientists are sneaky liars (and, in the “COVID as a bioweapon” version of the lab leak theory, saboteurs) who either accidentally or deliberately leaked SARS-CoV-2 from the WIV lab and then engaged in a massive (and now 2 1/2-year long) coverup. Now, you might say, even independent of the merit or lack thereof of the lab leak theory, blaming China for the pandemic is obviously irrational. China took effective steps to contain COVID, minimizing both their own deaths/illnesses and the number of infected people that left the country, whereas the US completely bungled its attempt to deal with the initially small number of cases that came here from China and elsewhere, and China is not responsible for that. That’s true, but rationality is beside the point; the point is to portray China in an unflattering light.

There is also a great deal of ignorance and an unwillingness to look into things in any depth. Largely irrespective of political orientation or media affiliation, the vast majority of journalists/commentators who have opined about the origins of COVID are unfamiliar with 90% or more of the information I presented in the previous section. To give an illustrative example, recently, in preparation for this article and the similar video I made recently, I watched a segment of Rising in which regular commentators Ryan Grim, Emily Jashinsky, Robby Soave, and Briahna Joy Gray (Bernie Sanders’ former press secretary) opined on the same Science journal articles that I discussed in the previous section. It was plain as day that none of the four had read the papers or understood any of the points the authors were making. I could understand if someone’s eyes glazed over while reading Pekar et al., because it was very technical and difficult for a layperson to understand, but for fuck’s sake, if you call yourself a journalist, at least try, so that you can summarize the main point and understand its significance. As for Worobey et al., although if you’re not a scientist you may not understand the statistical lingo, the basic points are very easy for an educated layperson to understand; Ryan, Briahna, Emily, and Robby, there is no excuse!

You might be wondering, if these commentators made a 15-minute segment about scientific papers they haven’t read, what did they talk about? Well, essentially, it was 15 minutes of speculation, gainsaying, talking in circles, and patting themselves on the back for their supposedly being better critical thinkers than either wing of the mainstream media (which they somehow are not part of despite doing a news show hosted by a giant corporation) who are willing to question the “establishment”—and, oh, there was also Ryan Grim demonstrating his ignorance about COVID by claiming that the virus had “evolved into a milder version”—as opposed to, you know, there being a vaccine for it that many people have gotten by now. What little they had to say about the studies themselves demonstrated that they were utterly unfamiliar with the details of the studies—for instance, they claimed that all the Worobey et al. study had demonstrated was that the Huanan market was “the earliest superspreader event” but somehow wasn’t the origin of the COVID outbreak. I’m not sure how “the earliest superspreader event” being immediately followed by the mushrooming of cases in Wuhan and then the world isn’t by definition the origin of COVID’s spread, but in any case, as discussed previously, it was precisely one of the main points of the study that it made no sense for the Huanan market to be a superspreader site at all unless it was so because of the presence of animals infected with COVID: There were hundreds of other sites that were much more frequently visited by humans.

In an amazing demonstration of both ignorance of the study and ignorance of Chinese culture, Grim claimed that there could only be compelling evidence of the market being the origin of the outbreak if there were a positive test of an animal or “even some fecal sample” (I guess positive tests of environmental samples only in areas where live animals had been sold and nowhere else in the market doesn’t count?) “to show that like, okay, you know, here is the animal it jumped from, here is this bat, and this bat was in the wet market…” Well, you know Ryan, there were no bats in the Huanan market or any other animal market in China that I know of, because Chinese people don’t eat bats!

Some lab leak theory proponents maintain that believing the pandemic was initiated by a lab leak is no more damning of Chinese people than believing that it began in the Huanan market. I guess if you believe that the pandemic began because Chinese people are disgusting bat-eaters, maybe that’s true. However, all that’s inherently required to believe that the COVID pandemic began at the Huanan market is that the Chinese government has not done a good job of enforcing its laws about illegal sales of wild animals (especially those susceptible to diseases caused by coronaviruses) in markets, and that China, like everywhere else in the world, has a problem with encroaching on forests and other wild animal habitat due to development, the forestry and mining industries, and animal agriculture (the world’s leading destroyer of forests). It doesn’t require you to believe that Chinese government officials or scientists are sneaky liars despite zero evidence that they are covering up a lab leak and an abundance of evidence that the emergence of COVID happened exactly how they have been saying it did for 2.5 years (and which led them to immediately close the Huanan market). In other words, the theory of zoonotic origin and emergence in a wet market is not a conspiracy theory; the lab leak theory is.

But, to put on my psychologist hat for a moment, why are people so prone to believe in conspiracy theories—even when they lack evidence to support them—in the first place? You may have noticed that people who subscribe to one conspiracy theory often subscribe to others as well. It’s been my observation, for instance, that people who subscribe to the lab leak theory are more likely than the average person to believe that masks and lockdowns are merely government efforts to control us that don’t/didn’t work to prevent COVID, and/or that COVID vaccines are basically a scam to increase “Big Pharma” profits and are ineffective or even dangerous, or even that the government exaggerated the severity of COVID to frighten and control us. (I’m assuming that if you’ve read this far, you don’t believe any of these things.) They are also more likely to believe conspiracy theories unrelated to COVID, such as that the 2020 election was stolen from Trump.

Arie Kruglanski, a social psychologist who has studied extremism and belief in conspiracy theories, argues that individuals who subscribe to them are particularly strongly motivated by a drive that he calls the “quest for significance,” a motivation to achieve respect, dignity, and purpose. Thus, whatever their overall orientation, believers in conspiracy theories are motivated to see themselves as special, unique, and "in the know." And they appear to have a strong need for certainty and closure, a desire for simple, black and white explanations and an aversion to nuanced, complex interpretations of reality or reconsideration of their point of view. A third factor Kruglanski identifies as important is that people who have beliefs that differ from the mainstream tend to surround themselves almost exclusively with people who believe as they do. However, he notes, this is only a more extreme version of the usual tendency that humans, as quintessentially social beings, to have beliefs that correspond closely to those of whoever is in our social circle, because they are by far the people whose beliefs we are exposed to the most. We also, of course, are exposed repeatedly to certain information from whatever media we consume. Repeated exposure to a given claim, whether from our friends or from the media, tends to lead us to believe it, even if it’s not accompanied by any supporting evidence—the so-called validity effect, or illusory truth effect. And when it’s from both sources, the result is mass belief in something with no supporting evidence: Instead of a few people believing very strongly that “the moon landing wasn’t real,” we have millions of people believing that “Iraq has weapons of mass destruction,” or “the COVID pandemic resulted from a lab leak.”

Conclusion

For those of us not prone to believing in conspiracy theories, nor making significant sums of money from stoking controversy, the body of evidence points strongly to the conclusion that, as with every other coronavirus that infects humans, SARS-CoV-2 passed over to humans from animals. That is what the overwhelming majority of Chinese and other scientists who have studied the issue have said was likely the case from the very beginning, and now there’s an abundance of evidence consistent with the Huanan market being the primary origin of the COVID outbreak and none consistent with it being a lab leak from the Wuhan Institute of Virology or anywhere else. If you want to still say in spite of all the evidence that’s come out and in spite of what Chinese scientists themselves have said regarding there not being any evidence connecting it with their labs, you’re necessarily accusing Chinese scientists of being liars; you're playing into Cold War propaganda, and speculating without evidence that there’s been a vast coverup. That’s pretty much what one would expect from China-bashers like some of the journalists I’ve discussed, or from those who are prone to subscribing to conspiracy theories because it makes them feel “cool” and “with it” to believe in them and because they hear them repeated over and over within their social circles, but if you take a scientific approach to the world and base your opinions on the evidence, at this point the evidence points overwhelmingly toward the conclusion that this virus, like many others before it, burst onto the scene and caused an epidemic (and pandemic in this case) because of animal spillover—and, as Pekar et al.’s study suggests, probably more than one—in the Huanan market.