Evidence Regarding COVID's Origins: A Summary

Polls show that the majority of Americans believe that COVID originated with a lab leak. But the evidence overwhelmingly points to animal markets in Wuhan.

Ever since the first COVID cases were detected in Wuhan, a huge city in Hubei province in east-central China, in December 2019, there has been a massive amount of speculation about its origins. As I wrote last year,

From the very beginning, the Trump administration and its allies in Congress and the far-right corporate media promoted the claim that the COVID pandemic came about through a leak from the Wuhan Institute of Virology lab rather than the Huanan market, where the first known cases had appeared.

Ultimately, as these sorts of claims pinballed around in the media and social media, support for this claim snowballed to include the majority of Americans. But what does the evidence say? In this article, I briefly summarize it.

How China Responded to the Wuhan Outbreak of December 2019

Before I get to the bulk of the evidence, it’s worth taking a look at how Chinese public health officials and the Wuhan city government and national government responded to the emergence of COVID in Wuhan, China. After the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission received reports in late December 2019 from area hospitals about a mysterious “pneumonia” in which 27 of 41 infected patients either worked at or had visited the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in downtown Wuhan, on January 1, 2020, the Chinese Centers for Disease Control closed down the market permanently. In addition, the CCDC took hundreds of environmental samples, 33 of which tested positive for the SARS-CoV-2 virus on its newly-developed PCR test.

Later that month, the CCDC published a report in which they concluded that they were pretty certain the Wuhan outbreak was associated with the (largely illegal even then) wildlife trade, which until that point had been a $74 billion a year industry in China. Shortly thereafter, the wildlife trade was shut down almost completely, first in Wuhan and soon thereafter in China as a whole. Eating wildlife was made illegal as well, and farmers who raised and bred wild animal species were offered cash to switch to a different line of work.

And, as I’ve written about here before, China proceeded to implement the most comprehensive COVID infection prevention program of any country in the world, which was wildly successful in preventing COVID infections and deaths until it was ended in late 2022, at which point about 92% of the population was fully vaccinated. China’s government can be faulted for not acting soon enough to shut down traffic in and out of Wuhan, Hubei province, or the nation, or implement lockdowns in highly COVID-affected areas—that did not happen until January 23. Despite that error, as I have written about here before, it locked down much more quickly following the onset of the outbreak than Western countries did, and acted far more effectively to control COVID.

In short, there is every reason in the world to think that the Chinese government made a sincere effort to control COVID infections as well as it could. If it had any evidence that the lab rather than the market was the most likely origin of the outbreak, it would have closed down the lab on Jan. 1, not the market and the wildlife trade. But that isn’t what happened. Acting on the evidence it had available regarding where early cases came from, as well as undoubtedly the precedent of SARS having erupted in animal markets in 2002, it closed down the market, not (until Jan. 23 when Wuhan as a whole locked down) the lab. So, let’s turn to looking at the evidence available then as well as that which has emerged over the past 3 1/2 years.

Precedent

The vast majority of viruses that infect humans, including all previously known coronaviruses that do so (SARS, MERS, various viruses that cause “colds”), are of zoonotic origin—that is, they originated when other species of animals infected humans. The main animal reservoir of coronaviruses is horseshoe bats, which have a wide range that includes much of Southeast Asia, including Hubei province where Wuhan is located, as well as Yunnan province where the evidence suggests SARS evolved.

There are many similarities in the emergence of SARS and COVID. They both began infecting humans (that we know of) in November, in major cities (Foshan in the case of SARS; Wuhan in the case of SARS-CoV-2). The animals that were found to be the intermediate hosts for SARS were also present in Wuhan markets up until at least November 2019, when SARS-CoV-2 started to show up in humans. It was found that some of the animals infected with SARS had been raised on animal farms in Hubei province. In fact, the largest suppliers of these animals to the Foshan area were farms in Hubei. The spillover of SARS was known to have occurred in wet markets that sold live mammals known to commonly carry coronaviruses, such as palm civets and raccoon dogs, as some of these mammals in fact tested positive for SARS; moreover, SARS was found in Hubei province, both on farms and among animals in the wild. The same sorts of wild mammals not only were for sale in Wuhan wet markets shortly before the pandemic, but were often supplied to those markets by farms in Hubei province.

Building Blocks

Viruses fairly closely related to both SARS-CoV-1 (the virus that causes SARS) and SARS-CoV-2 have been found in bats and pangolins (a type of anteater) throughout Southeast Asia, particularly though not only in Yunnan province in Southern China as well as neighboring Laos. In terms of their overall genetic makeup, these viruses still have considerable differences from SARS-CoV-2 (up to 97% similarity, which is less similar percentage-wise than pigs’ genetic makeup is to humans’), but crucially, some of them are similar in a key area of the virus called the receptor binding domain (the part of the virus that attaches to animal cell receptors), and some have a furin cleavage site, a feature of some coronavirus’ structure associated with cleavage of spike proteins by furin (an enzyme) that facilitates its ability to enter and infect cells, and is thought to be an important aspect of SARS-CoV-2’s infectiousness.

Early Cases

As noted previously, 27 of the 41 earliest known cases of COVID were among people who either had worked at or visited the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market. The majority (93, 55.4%) of the 168 confirmed cases in December 2019 were people who had visited or worked at either the Huanan Market or other animal markets in Wuhan. Fifty-five of these 168 cases were in people who had worked at or visited the Huanan Market.

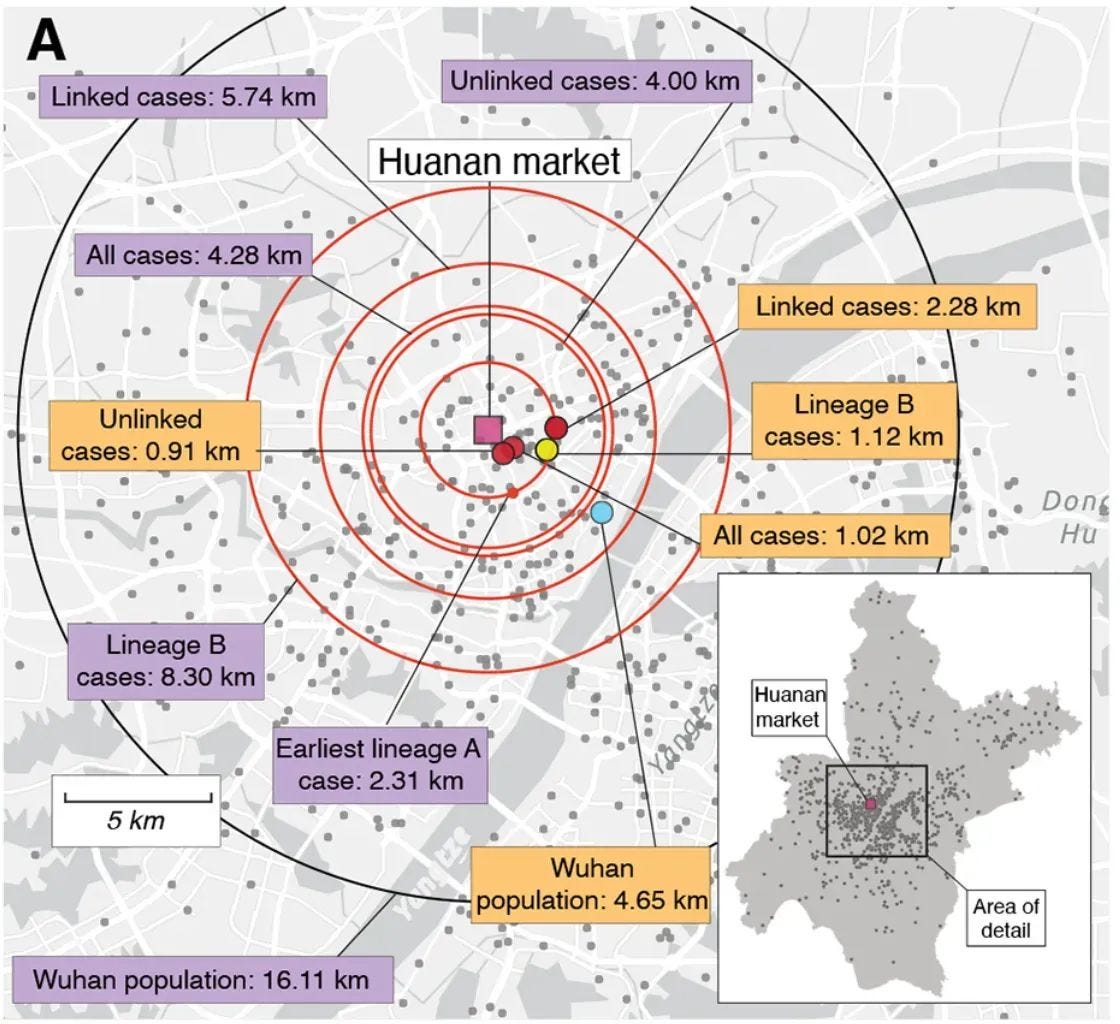

Not only early cases, but early hospitalizations and deaths, were strongly associated with the Huanan Market (i.e., in most cases, either their place of residence was nearby, or they had worked at or visited the market), and prevalence of antibodies for SARS-CoV-2 was highest in the neighborhood surrounding the Huanan Market (see figure).

The residence of 155 of the 168 confirmed December cases of COVID was known from clinic or hospital records, and where they lived clustered around Huanan Market. Whereas the average Wuhan resident lived 16.11 km from the market, the average person infected with COVID in December with no connection to the market lived only 4 km away; the average person who had a connection to the market lived 5.74 km away. There was vastly greater than a chance difference between the average

distance uninfected vs. infected people lived from the market, and there was also a vastly greater than chance difference between how far away the market-connected and market-unconnected cases lived. The fact that infected people who had no connection to the market lived closer to the market than infected people who did have a connection to the market shows that the virus spread through the neighborhoods surrounding the market. (Very few of these early cases were anywhere near the lab, which is 7.5 miles away.)

This initial outbreak that was so strongly associated with the Huanan Market was no mere superspreader event. There are hundreds of locations in Wuhan (shops/shopping centers, hospitals, workplaces, universities, churches, etc.) that have more public traffic than the Huanan Market, yet none of them had large numbers of cases traceable to them. The only other places that had a significant number of early cases were other animal markets (again, 93 of 168 early cases, 55.4%, were associated with one of four markets in Wuhan that sold live mammals, and 55 (32.7%) were associated with Huanan). About 70 other markets in Wuhan have more traffic than any of these four. The association of early cases so overwhelmingly with markets that sold live mammals is no mere coincidence. And it’s highly incompatible with the idea that the virus leaked from the Wuhan Institute of Virology (several miles away from the Huanan market). Infected lab employees would have had to have visited these four animal markets, which aren’t even close to the most frequently visited places in Wuhan, almost exclusively and not been going to those hundreds of other places to account for the fact that the majority of early cases were tied to markets that sold live mammals. And this would have had to happen at least two times, given that molecular analysis indicated that there were two separate spillovers, beginning about a week apart and involving two slightly different viral variants, associated with the Huanan market.

The clustering around the market disappears as the Wuhan outbreak is tracked through time, with cases spread out all over Wuhan, particularly in densely populated areas, by mid to late January—as indicated by location data for individuals who sought help on the COVID assistance channel of a Chinese social media platform.

The Southwest Corner

Animals known to be susceptible to coronaviruses were documented (observed and photographed) to have been sold in stalls in the southwest corner of the market, which is also where environmental samples of SARS-CoV-2 from the market were found the most. Those environmental samples tended to be in cages where live mammals had been observed to have been kept, or on carts that were used to move animals around. (One exception was a chicken feather remover, which was located next to one of the aforementioned cages.) Later research found that DNA from raccoon dogs was present in an environmental sample from one of these carts. [Note: That research was published a few months after I wrote this piece.]

What About The Lab?

As I noted in the introduction, the notion that the virus leaked from the lab remains highly popular despite the emergence of all the evidence I have described above that is much more consistent with the idea that COVID emerged from animal markets than with the idea that it emerged from the Wuhan Institute of Virology or any other lab. But what information do we have that directly suggests the lab was not involved?

First, in an interview with the journal Science, Dr. Shi Zhengli, director of the WIV’s emerging infectious diseases lab and leader of the team that discovered the bat populations in which the SARS-CoV-1 virus originated, stated that all WIV staff had been tested for COVID early in the Wuhan outbreak and had all tested negative. Shi also stated that the WIV did not have either SARS-CoV-2 or any viruses similar enough to it in its possession that could have served as building blocks for its creation. Consistent with this claim, there is no record anywhere—not in scientific publications or preprints and not in databases—of such viruses existing in any lab in the world prior to the discovery of the virus in early January 2020. Of course, people can claim and have claimed that Chinese scientists such as Shi are lying, but an unsubstantiated claim that someone is not telling the truth is not exactly evidence.

At any rate, US intelligence agencies recently released a report of the investigation by some of them of the possibility of a lab leak, and asserted that they could not find any evidence that SARS-CoV-2 was genetically engineered or developed as a bioweapon by the WIV, and that the research reported to be conducted on coronaviruses there was with viruses “too distantly related to have led to the creation of SARS-CoV-2.” Elsewhere in the report, they elaborated on this:

Prior to the pandemic, we assess WIV scientists conducted extensive research on coronaviruses, which included animal sampling and genetic analysis. We continue to have no indication that the WIV’s pre-pandemic research holdings included SARSCoV-2 or a close progenitor, nor any direct evidence that a specific research-related incident occurred involving WIV personnel before the pandemic that could have caused the COVID pandemic.

A further issue addressed by the US intelligence community report is the claim (made by anonymous US government officials and reported initially in the Wall Street Journal) that three researchers at WIV fell ill in November 2019 with mild respiratory symptoms that could have been COVID, and visited a hospital clinic for treatment (routine medical treatment is often provided at hospitals in China). According to the report, there is no indication that these individuals were hospitalized or any information to indicate that any of them actually had COVID, and their symptoms were consistent with those of other respiratory ailments such as colds or allergy symptoms. In addition, there was an influenza outbreak in Wuhan in early November. It seems likely that among the hundreds of WIV staff, somebody would have gotten the flu.

Conclusion

All in all, the above-described evidence is quite parsimoniously explained in terms of the theory that the Wuhan COVID outbreak in December 2019 began at the Huanan Market and that the ultimate source of the SARS-CoV-2 virus is either bats in caves somewhere in Southeast Asia or wild mammals that are often raised on farms relatively near Wuhan and sold in markets there, and almost impossible to reconcile with the view that SARS-CoV-2 was somehow leaked from the WIV lab. Despite that, to this day, scientists who have investigated COVID origins maintain that although a lab leak is highly implausible given the current evidence, it is not impossible and they would change their minds if, for example, it emerged that the WIV did have SARS-CoV-2 in its possession prior to Wuhan’s outbreak. It seems that this sort of open-mindedness, a universal trait among good scientists, is not typically shared by lab leak proponents.

One reason why is that, although it’s not true of all of them, it seems very common among prominent lab leak proponents (Michael Shellenberger, Donald Trump, Josh Rogin, Jamie Metzl, etc.) to be extremely anti-China, leading them to be predisposed to accept any “China bad” claim/conspiracy theory uncritically. Of course, claiming that COVID resulted from SARS-CoV-2 leaking from the WIV is not inherently more disparaging of China than claiming that its enforcement of laws regarding animal markets was lax prior to the COVID outbreak, nor are lab leak claims inherently conspiracy theories. However, lab leak claims that persist 3 1/2 years later despite all of the above evidence are inherently claims that the Chinese government and/or scientists who investigate viral origins are covering something up—the essence of a conspiracy theory.

Furthermore, not only are they inconsistent with the direct evidence about where Wuhan’s outbreak began, but they are also inconsistent with various known facts about Chinese government policy in general. As even many of those with highly negative views of the Chinese government (which most Americans have) can acknowledge if they look at the evidence, China’s government has acted pragmatically in many ways that have greatly benefited the majority of its citizens. As acknowledged by the World Bank and many others, China has lifted 800 million people out of extreme poverty over the past few decades. Chinese life expectancy has now surpassed that of the US; China has universal healthcare; 90% of Chinese adults own homes; China produces the majority of the world’s electric vehicles, solar panels, and wind turbines, and accounts for 2/3 of the world’s high-speed rail mileage. So why would Chinese officials have only acted to cover up where COVID came from, rather than acting in a manner consistent with trying to protect its citizens from it (which, as described above, it’s done in a more comprehensive and successful way than virtually every other country), which would include trying to shut down what evidence at the time suggested was the original wellspring of the outbreak, the wild animal trade? As I said at the beginning, if they had any evidence that the lab rather than the market was the most likely origin of the outbreak, they would have closed down the lab on Jan. 1, not the market. But that isn’t what happened. On Jan. 1, 2020, Chinese public health officials closed down the Huanan Market, because that’s what the evidence suggested they should do.